This review originally appeared in ARTORONTO.CA in December 2019

‘They can’t see the forest for the trees’ is an expression applied to someone who can’t understand the whole because they’re too engrossed in the parts. This conventional wisdom elevates the understanding of patterns over the focus on particulars. Hugh Alcock’s work suggests the opposite: he argues for the virtue of detail. In his show at Gallery 1313, he brings out attention to bear on the intricate patterns and textures within forests.

Installation view of Hugh Alcock, In the Dusk of the Woods in the Cell Gallery at Gallery 1313

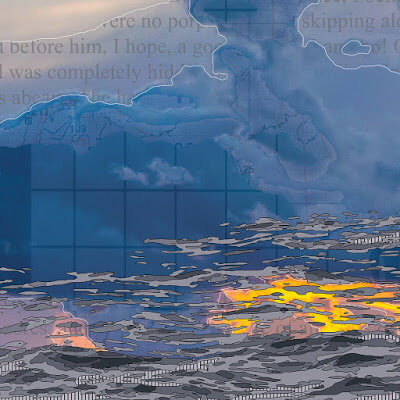

Alcock’s installation asks us to follow the artist in looking very closely at trees. Large drawings adorn the walls of the gallery and a wood and burlap sculptural figure stands on the floor. The drawings are heavily worked with several layers of chalk, charcoal, and subtle hints of colour. In these images, we are in the midst of dense thickets and undergrowth. It’s the kind of forest where we push through branches that reach out to scratch skin and catch clothes. We’re deep inside the forest, only glimpsing fragments of sky while dense vegetation limits our vision to foreground details.

“Glen Nevis, Scotland”, 2019, pastel and charcoal on paper, 40 x 64 in

There is a serenity and stillness in these images and yet the linework and geometry in Alcock’s depictions illustrate that there’s a dynamic living process at work, if at a pace and timescale that we cannot perceive.

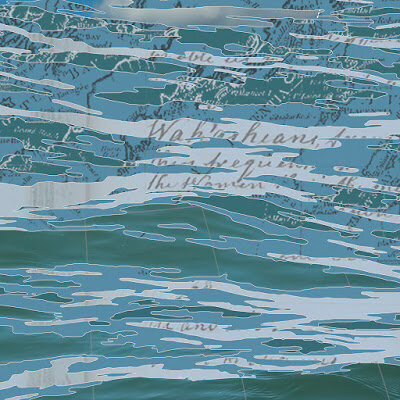

Alcock bases these drawings on photographs taken during walks in the woods. Often, elements from different photos have been combined into one drawing. Each drawing starts with a thin wash of pigment over thick watercolour paper. This background sets the general colour cast of the image and informs some of the layout. In “Dead Tree, Rouge Valley” for example, drips and streaks in the pigment determine the arrangement of the trees and branches. He builds up detail with dark charcoal lines and white pastel as well as a restrained application of greens and browns.

“Dead Tree, Rouge Valley”, 2019, pastel and charcoal on paper, 40 x 60 in

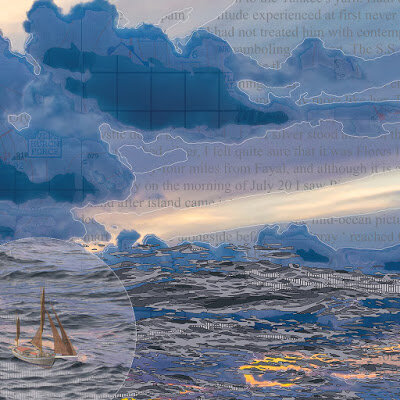

Alcock explains that his work reflects a careful study of the forest rather than an expression of personal artistic intent. His work closely examines the shape and texture of branches, bark and leaves while resisting the conventional constructs of what we might expect ‘beautiful landscapes’ to be. Alcock see trees as “emblematic of the natural world, that is, the world independent of us and our narrow interests and preoccupations.”

“Devon Woods”, 2018, pastel and charcoal on paper, 36 x 50 in

More recently, Alcock has extended his interest in trees to the production of sculptures, one of which occupies the floor of the gallery. Alcock collects sticks and small branches that he finds interesting. He feels that each fragmentary piece tells a story – it shows the history of its growth and development; it hints at how it fit into the larger system of a tree. He arranges these individual sticks into groups and assemblies according to his own particular aesthetic and structural rules. The structures are held together with simple hardware and are then fleshed out with burlap fabric and baling twine. Of these assemblies, the artist says that they “resemble animated creatures. Maybe they are manifestations of what in mythology are called ‘tree spirits’ or ‘drayads’.”

“Sculpture, Untitled # 2”, 2019, wood burlap and twine, 34 x 36 x 64 in

Again, as in the drawings, the work evolves through the careful study of trees and branches. The sculptures are the result of the materials and the rules of the process. The artist acts more like the editor rather than simply the author of the work.

“Forest, Dorset”, 2018, pastel and charcoal on paper, 36 x 72 in

Alcock acknowledges the irony of presenting an experience of nature in the mediated and sanitized environment of a gallery. He emphasizes that the work is not intended as a simulation of nature, but rather a study of it. Unlike photography, a drawing gives us insight into how an artist has experienced a scene. As we follow the lines and marks, we’re following the perception of the artist and for a moment we can see the world through somebody else’s eyes. This aspect of drawings, this borrowed vision, can only help enrich our own experience and bring us closer to see the world as it exists “independent of us.”

Text and photo: Mikael Sandblom

*Exhibition information: December 4 – 15, 2019, Gallery 1313, 1313 Queen St W, Toronto. Gallery hours: Tue – Sun, 1 – 6 pm.