Lost Horizon Spray

His boat, 'Spray' was so well balanced and Slocum was so good at setting her sails that the little vessel could stay on course for hours on end with the wheel lashed. He described his adventures in his famous book "Sailing Alone Around the World"

The ghostly text that appears in this picture describes an episode during which, suffering from food poisoning, Slocum hallucinates a member of Christopher Columbus crew steering the Spray safely through a storm.

En Route to Howland Island

John Hartman at Nicholas Metivier Gallery

This review originally appeared in ARTORONTO.CA in November 2018

John Hartman is a painter and a storyteller. Ask him, and he’ll tell you about every detail in his paintings. Each pictorial element helps describe a place and the people connected to it. His latest body of work is focused on other Canadian storytellers and the places that are important to them.

“These are the most realistic paintings I can make”, says Hartman of his new portrait / landscape paintings. Realistic in this case is not the ‘realism’ of photography or renaissance perspective. These paintings are realistic in the sense that they express the character of people and their relationship to special places.

John Hartman explains Ian Brown, Go Home Bay. Photo: Mikael Sandblom

In the People and Place paintings, Hartman has painted the portraits of several Canadian writers including Ian Brown, David Adams Richards, Esi Edugyan, Lisa Moore, Linden MacIntyre, to name a few. Each author appears to float in the air above a landscape that Hartman has asked them to choose: a place that may not necessarily be their home town but inspires them and restores them.

John Hartman, Linden MacIntyre Above Little Judique Harbour, 2018, oil on linen, 60” x 66”. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Hartman starts by documenting both his subject and their chosen place. A series of photos of the writer are lit from various angles to allow him to match the direction of light in the landscape. In addition to making sketches, he photographs the landscape location with a drone to get the aerial perspectives that are so pervasive in his work. He’s careful to record all the aspects of the place that are meaningful to his subject.

Hartman plans the painting with red outlines on the canvas. Typically, the view is from above, the horizon is in the upper quarter of the painting, and the figure is shown below the horizon. He distorts the landscape around the figure to emphasize important features, ensuring meaningful details are not hidden. In some paintings there are additional elements that float in the space behind the foreground figure such as the devil falling to earth in David Adams Richards above the Bartibog and Miramachi Rivers. Hartman works and rearranges this line drawing until he is satisfied with the composition and the narrative.

Detail from John Hartman, David Adams Richards above the Bartibog and Miramachi Rivers. Photo: Mikael Sandblom

Once he has finalized the composition the colours are applied. He paints in oils with energetic and expressive brushwork. He starts at the top of the canvas and works his way down, painting wet-on-wet allowing the colours to blend with the brushstrokes. Using the same colour palette in the figure and the background establishes a visual connection between the two. He’ll adjust tone and colour in the background to ensure there is always a clear edge between the figure and the landscape.

Detail from John Hartman, Lisa Moore Broad Cove. Photo: Mikael Sandblom

The figures are larger than life, brightly lit and delineated in broad brush strokes. Hartman likes to paint people older than 45 when “your face tells the whole story and you can’t pretend to be anyone other than who you are”. These are not always flattering portraits, but they express personality and mood. David Adams Richards looks out to the space behind us. Esi Edugyan looks upward and to the side. The impression is of deep thought, as though they have let their minds wander and fly out over the landscape of their imagination.

John Hartman, Esi Edugyan, Victoria, 2018, oil on linen, 48″ x 54″. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Once a painting is completed, he sends a photo to the writer and asks them for a short text describing the place and its meaning. These companion texts have been mounted on the wall next to the paintings. The descriptions will appear on the facing page of each image in a book that is being planned in conjunction with a traveling museum exhibition, which is scheduled to start in November 2019.

Hartman sees his paintings as part of an effort to re-establish the narrative and descriptive role of painting that he feels was conceded to film and photography in the last century. He has been working on this project for three years and he feels that he’s found a direction that opens more possibilities the further he pursues it.

Mikael Sandblom

*Exhibition information: John Hartman, People and place, November 8 – December 8, 2018, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, 190 Richmond Street East, Toronto. Gallery hours: Tue – Fri, 10 am – 6 pm; Sat, 12 – 5 pm.

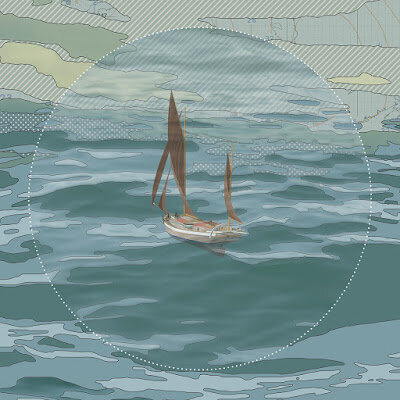

Theseus' Paradox

Theseus' paradox is based on the story of Theseus' ship. The Greek hero's ship was kept for a hundred years and continually repaired so that eventually all the original planks and timbers were replaced. The question is: is this ship, with no original parts, the same ship? is it still Theseus' ship?

Like Theseus' ship, our little boat of life needs to be constantly maintained, adapted and updated. That which will keep us afloat tomorrow is not what kept us afloat yesterday.

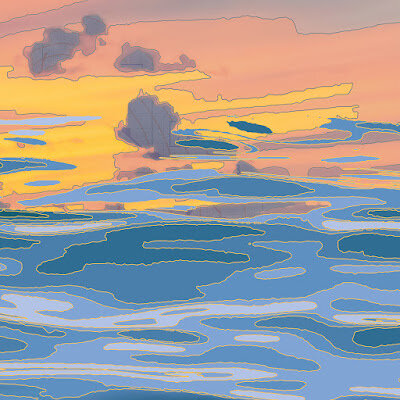

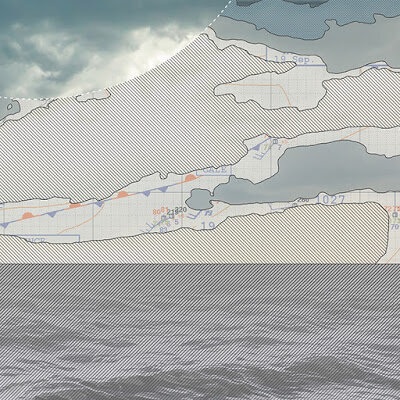

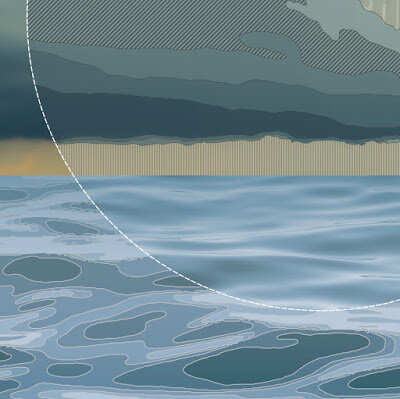

Groundswell

A ground swell is a broad, deep undulation of the ocean caused by a distant storm. Powerful waves travel for great distances long after the originating tempest has been exhausted. Ships and shores are pulled and pushed by the effects of unseen storms.

The ground swell is a metaphor for the impermanence of the world. Forces both seen and unseen ensure that nothing in this world lasts forever. What feels solid and permanent is inevitable exposed to be ephemeral and temporary.

"Then I looked on all the works that my hands had done

And on the labor in which I had toiled;

And indeed all was vanity and grasping for the wind."

- Ecclesiastes

Standing on solid ground is an illusion. We've always been floating on an ocean.

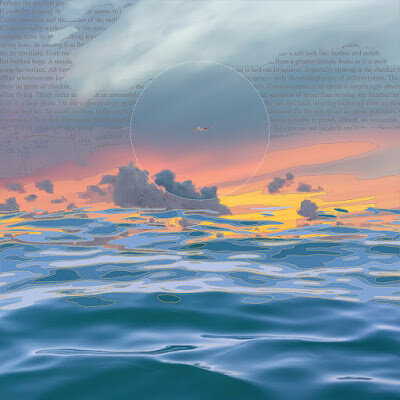

Phosphenes

When the light are bright, we trust our eyes. We believe what we see. Or do we see what we believe. How much of what we observe really is from the outside world? Do we see only what we expect to see?

Our vision is not passive. To see is to interpret; to project our ideas and memories; our fears and hopes onto whatever may be out there.

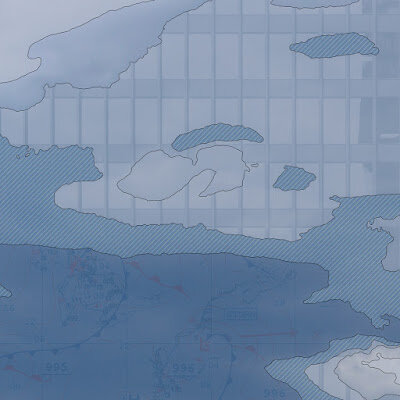

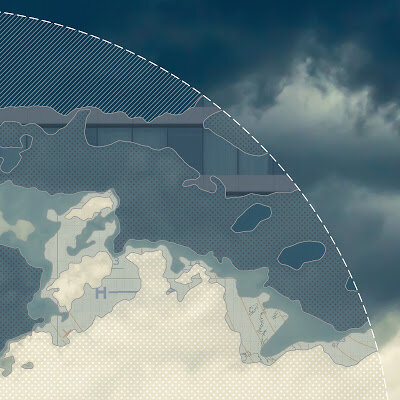

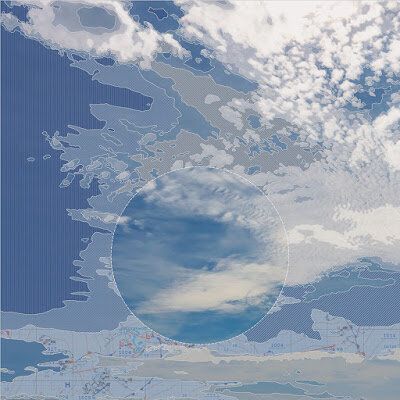

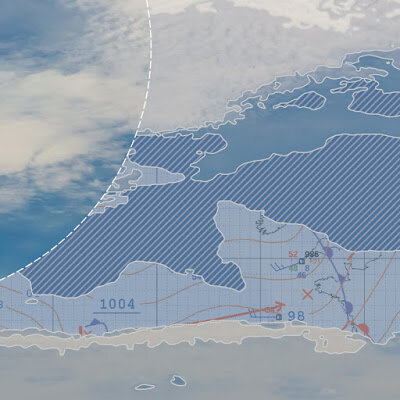

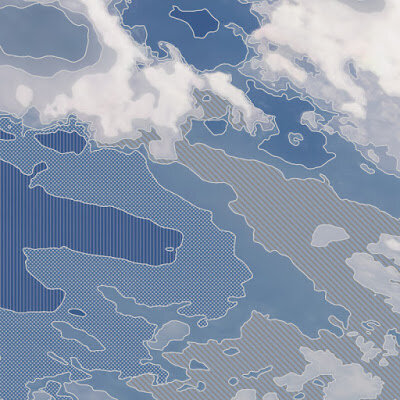

Ocean of Air

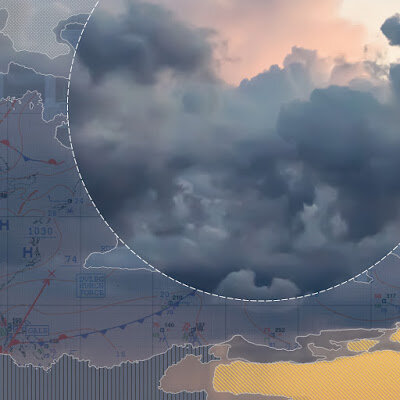

We live at the bottom of an ocean of air. It's 100 km deep. Although we can't feel it, this ocean is pressing down with 1 kg of weight on every square cm of the earth. This invisible ocean surrounds us. It protects and sustains us. The clouds in this image may be between 5 and 10 km above the surface of the earth - far above us, but still deep down in the ocean.

The cloud outlines look like coast-lines and archipelagos. The act of mapping and diagramming is analogous to how we navigate and make sense of the world.. In this image, there is a small 'lens' through which we see the clouds in full detail. The remaining peripheral area is filled with partial abstractions. These areas represent how we fill in our limited perception with ideas and constructs. To 'make sense' of the world, one inevitably must resort to over-simplifying it.

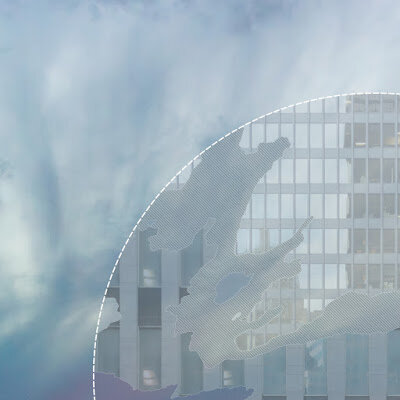

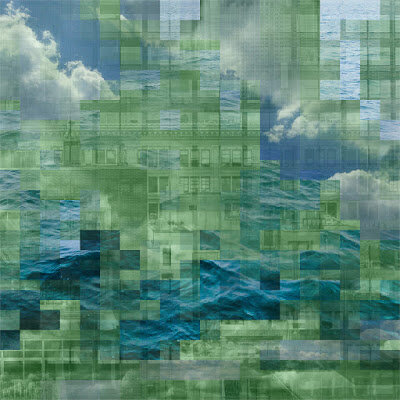

Mirror / Window

'Mirror / Window' is a piece that plays with the idea of perception and reflection. The ghostly images of buildings that appear in the sky partly reflect that same sky and within the shadows, reveal their interior.

An old text describes our perception of the world as a limited view through a dark mirror. In the brightness of day we might think our knowledge is firm; our apprehension is complete. In the twilight you start to doubt what is truly outside and what is a reflection of the inside.

Thunderstorm

- Thunderstorms form when warm moist air rises into cooler layers above.

- The clouds are over twelve kilometers tall.

- On average, they are over 20km in diameter.

- They lift 500 million kilograms of water vapor into the high atmosphere.

- Lightning bolts can contain up to a billion volts of electricity.

And yet, for all their power they are made only of mist. Each storm exists only for a few hours. Each one disappears leaving only a trace of damp in the ground and the fleeting glitter of raindrops on leaves. Being large and powerful provides no protection. Nothing lasts for long.

Squall

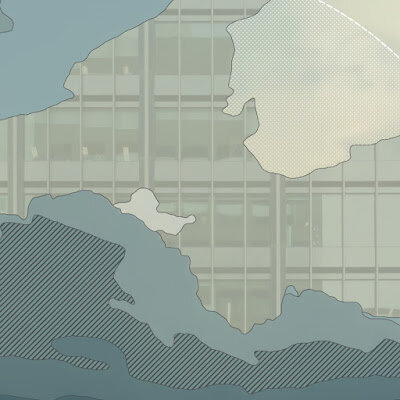

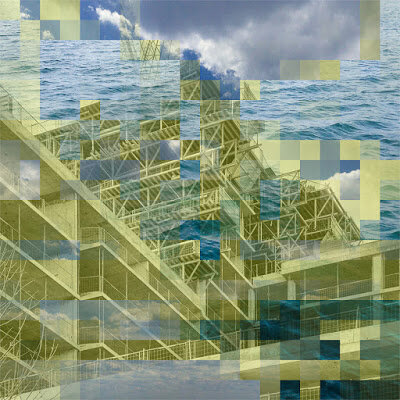

Cities and buildings are among of the most salient impressions that humans have put upon the world. They are a manifestation of ideas. What starts out as lines on a map: measurements and calculations take on solid form.

Underneath and through our delicate systems of grids and structure the wild forces still move. Like the erosion from underground streams or the sudden shock of tectonic movements, cosmic chaos ensure that the only true constant is change.

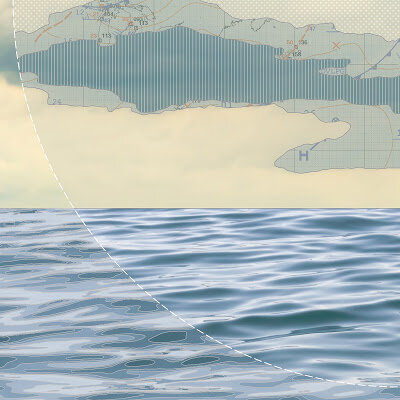

How Little We Know

The danger is that we forget that we've built a model and that we act as though the world actually is our over-simplified, model version.

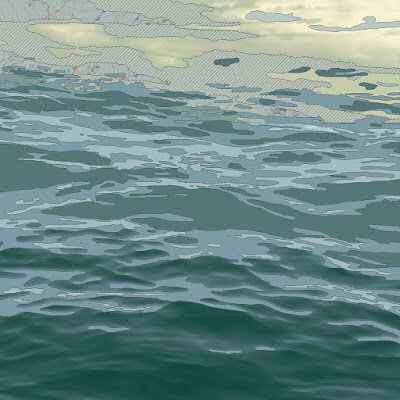

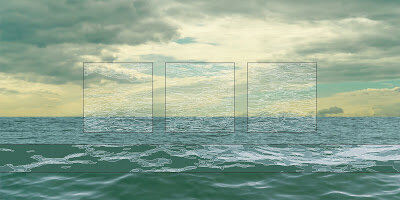

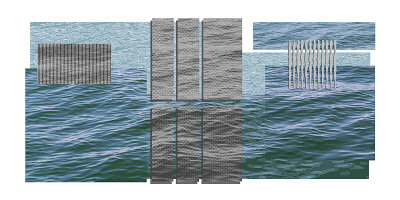

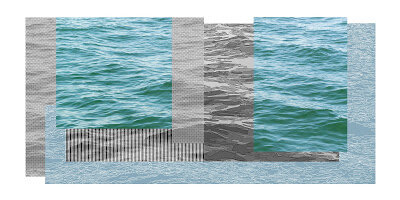

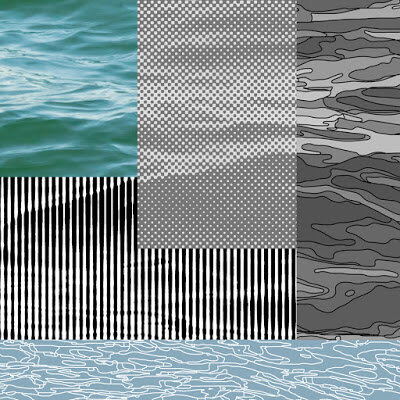

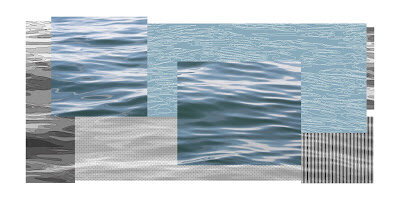

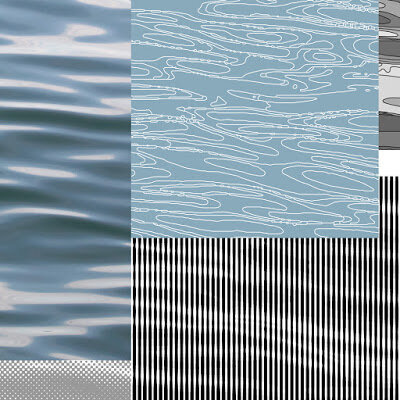

These water and cloud pieces are a meditation on the limitation of our understanding of even rudimentary things. The surface of water: how simple! In our mind's eye, we know exactly what that looks like. But the geometry is actually very complicated. There are undulating patterns that never actually repeat. Smaller and larger scales are superimposed over each other. Wave geometry is extremely intricate, even in a still image. Moving water waves in the real world are, to our minds, incomprehensible. We can look at waves, but we cannot fully 'see' them!

These artworks draw you in with the colour and 'natural beauty' of traditional landscapes. As you look closer you discover the graphic elements of outlines, tracings and other geometry. Reminiscent of contour maps and weather charts, these diagrams are attempts to document, regulate and explain the natural world - the process of model-making. Rather than clarify the natural patterns however, the analytic diagrams only emphasis their complexity.

In this age of glib thought and fast opinion; of simple answers to complex questions, it is important to question our tacit assumptions. In a gentle way, I think these pieces can inspire us to notice that the models that we necessarily use to make sense of the world are incomplete and contingent.

A Brief History

The early people came up with systems:

- Sounds could refer to ideas.

- Shapes could refer to sounds.

- Things could be counted.

- Lines could be used to measure and divide the earth.

When more people came to think in this systematic way, things had to change. Maps were drawn to reflect the earth and then the earth was changed to match up with the lines that were drawn on the maps.

Depth

Negative Time

The Right Angle

What does water look like?

There are so many waves and they're moving so fast. The shapes are really complicated and it's hard to make out the patterns.

So as artists do, I looked to other art for clues. It seems that no one got it right until photography was fully invented. We had to 'stop the world' before we could depict it.

The complexity of waves goes beyond geometry, it is also time-based. I've tried to follow just one wave as it moves through the others. I can't do it for long. I can look at water, but still not truly 'see' it.

Forgetting

The brain is always full. For a new memory to form, an old one must be forgotten.

You never know which memory was sacrificed because that's the nature of forgetting.

Are cities like human memories?

There's not enough room for all the buildings, so if we need a new one, we have to knock down an old one.

Every time you go by a new building, your awareness of it gets stronger and your memory of what was there before gets weaker.

Escape

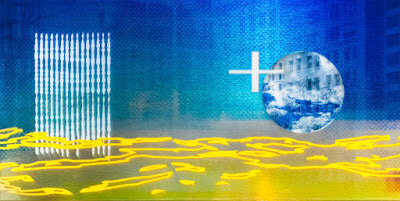

This painting is called 'Escape' after escapement, the part of a clock that controls the speed of the movement by allowing one cog of a wheel to escape at regular intervals, precisely regulating the rate of the clock.

In the painting, there are images of clock parts in the background and in the round 'window'. The yellow graphics over top are abstractions of cog wheels seen from the side. But these things are hard to see and not obvious.

There are abstracted clouds that appear and disappear. There's the green pattern of water surface reflections and the vertical lines that appear as water at a distance but dissolve on closer inspection.

The representational components invite the viewer to try and see a complete image but this effort is frustrated at every turn as attention is pulled away by other elements in the painting.

Spreading Skepticism

The meaning and purpose of the painting is to call attention to the impermanence of the world and to our vague and contingent grasp of it. The painting is meant to invite you in with a suggestion that you might figure it out, but then never quite let you feel confident that you've done so.The painting makes one self-conscious of trying to pin it down; self conscious of attempting to apply an 'interpretation' to what we see. This is what we un-consciously do in daily life to everything around us.

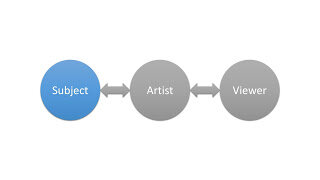

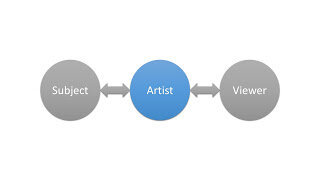

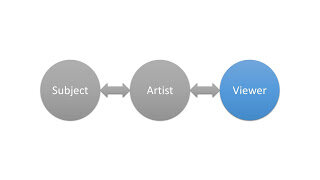

The Viewer Creates the Art

To categorize this painting, we could call it representational with aspects of abstraction and collage. In a representational painting, there are three components, the subject that is being depicted, the artist who creates the work and the viewer who experiences it. One can think of art that emphasizes various aspects of this relationship.Realist art strives to as accurately as possible depict the subject. In realist art, the artist attempts to be transparent; almost invisible. The realist artwork derives its meaning from the subject and how it is framed. in this mode of art, the artist records the subject and the viewer sees through the work to the subject and that which it signifies.

In expressionist art, the role of the artist is front and centre. The subject still exists as a reference, but the artwork is an idiosyncratic, distorted representation meant to express emotions or ideas of the artist. In this genre of art, the art does not signify what the subject is, so much what the artist wants to express.

In this painting, it is not the subject or the artist that is central but rather the viewer. Elements that are recognizable as visual representations of things and materials are arranged in such a way as to encourage an attempt at reading and interpretation. There are recurring symbolic themes, but many different interpretations are possible. In these paintings, it is the viewer that is central to the experience of the art.

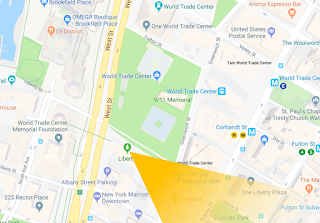

Ground Zero

The background of the image is a photograph from just south of the 9/11 memorial. It looks east towards a church under construction. From this location, the memorial is to the left. The motif of the vertical water pattern here refers to the waves that move through the streams of water as they fall into the monument. They also recall the ribs of the Calatrava train station just north of this place.

The water pattern at the bottom can refer to the water underground, held back by massive concrete walls that remain from the old World Trade Center complex. It could also refer to the island location and the precarious situation in the face of rising sea levels. As in previous paintings, the water image also reflects impermanence and constant change - particularly apt for this location.

The plus-sign or cross can refer to the Easter Orthodox church that is being built here but I also see it as the grid of the city which runs into the more chaotic older street pattern at this location. The right angle is the angle of the city street, of the buildings that is imposed over nature but which in the long run will be washed away.

The circular photo acts like a lens through which the background image can more clearly be seen. It's a small lens, it only sees through to a small part of the background. It also refers back to the pale blue dot that is the world.

None of these elements or interpretations are required to 'decode' the painting. Visually it stands on its own and viewers will have their own interpretations. It's loose enough to foster and accommodate a sense of mystery.

For me, as the artist, the use of specific meanings tied to a real place is an ordering system that prevents the painting and the constituent elements from becoming arbitrary.